In the first test of California’s Fugitive Slave Law , three formerly enslaved black men who had built a lucrative mining supply business were stripped of their freedom and deported back to Mississippi.

California Fugitive Slave Act of 1852: In 1852, pro-slavery forces in California pushed a law through the legislature that put many blacks at risk of being forcibly deported back to slaveholding states in the south – and to lives of brutal indentured servitude. There was already a federal law that gave slaveholders the right to reclaim enslaved men, women and children who fled the horrors of southern plantations to free states. It further required government officials to actively assist in their recapture whenever a slave “owner” filed a claim. California passed its own companion law. It decreed that any black person who arrived pre- official statehood as a slave (prior to September 1850 ) would be considered a slave in the eyes of the law. This even though the California constitution banned slavery and the state had come into the Union as a supposed “free state” under the Compromise of 1850. Many of the 2,000 black people living in California at that time had arrived as slaves during the Gold Rush from 1848-1850, which meant that their lives were in jeopardy. Slaveholders had one year to reclaim their “property” and leave the state. Any slave who ran away was treated as a criminal by the legal system, subject to be hunted down and returned to the slaveholder. The law, which had a sunset clause, was renewed until 1855, when it finally expired. It wasn’t just slaves who could be rounded up under these inhumane laws. Free blacks were also illegally kidnapped. When that happened, they had no way of defending themselves in court because there were laws that prohibited blacks from testifying against whites. It’s unknown how many free black people were illegally arrested and deported based on false accusations.

In 1849, Charles Perkins, a white Mississippian, set out for California to mine gold with an enslaved man named Carter Perkins. They were soon joined by two other male slaves from the Perkins plantation, Robert Perkins and Sandy Jones, who had been forced to migrate West, leaving their wives and children behind. The three men went to work for Charles Perkins mining gold.

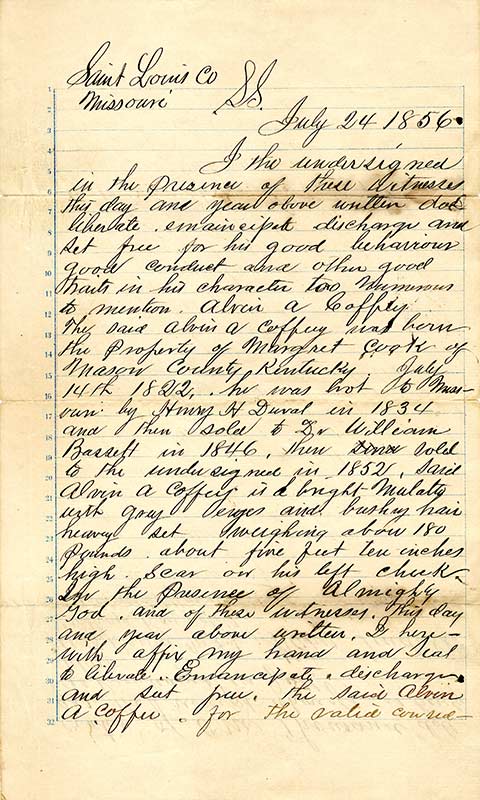

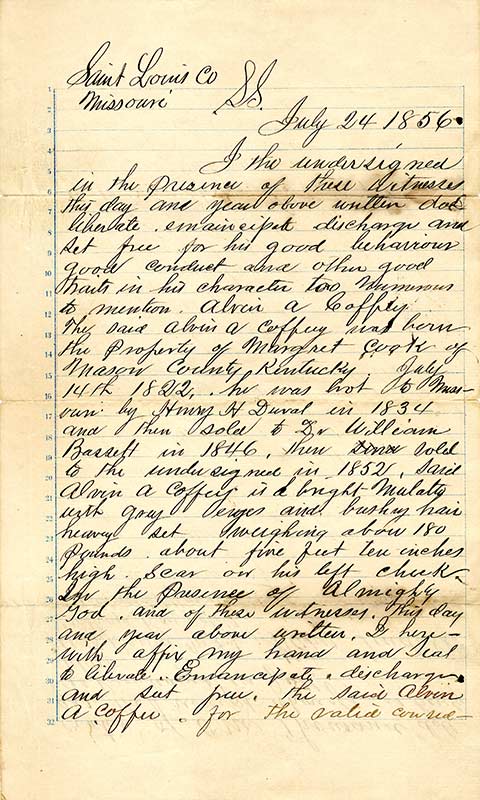

ALVIN COFFEY (1822-1902)

Gold mine earnings were a ticket to freedom for some formerly enslaved black men. In 1849, Alvin Coffey, 27, was brought to California by a white slaveholder from Missouri named Dr. William Bassett. Near Redding Springs, CA, Coffey mined for gold, earning $5,000 for Bassett and more than $1,000 for himself. Bassett, who was ill, decided to return to Missouri. Coffey nursed him all the way home. Once Bassett was safely delivered to his wife, he took Coffey’s hard-earned money and sold him away from his family. Coffey convinced Nelson Tindle, the second slaveholder, to let him return to California to mine for gold. Tindle agreed to free Coffey if he brought him back $1,500 – the purchase price Tindle set for Coffey. Coffey earned several thousand dollars in the mines and returned to Missouri to purchase his freedom and his family’s. The Coffeys returned to California and settled in Red Bluff, CA. Alvin Coffey later founded the first institution to provide care for elderly African American people. He is the only black person ever inducted into the Society of California Pioneers, whose membership includes direct descendants of California pioneers who settled in the state before January 1st, 1850.

Alvin Coffey’s manumission papers, 1856 Gift of Michele A. Thompson, Society of California Pioneers.

Charles Perkins decided to return to the South and left his slaves in the care of a friend. He agreed to release them on the condition that they work for six months longer. Set free in November 1851, the industrious trio—Carter Perkins, Robert Perkins and Sandy Jones—launched a business transporting mining supplies in the gold fields near Ophir. They earned the equivalent of $100,000 in today’s dollars. But in 1852, California lawmakers passed a law that decreed that any black person who had entered California as a slave before statehood was the legal property of the slaveholder who brought them. Shortly after the law’s passage, Charles Perkins filed a legal action in California, demanding the return of his human “property.” He wrote to a cousin who contacted the Placer County Sheriff, whose men seized Carter Perkins, Robert Perkins and Sandy Jones from their cabin in a midnight raid. A justice of the peace ordered the men deported to Mississippi. The black community mobilized, raising funds to fight for the men’s release. They hired Cornelius Cole, a prominent anti-slavery attorney, who argued before the state Supreme Court that since California’s Constitution banned slavery, the Fugitive Slave Law was unconstitutional. However, pro-slavery justices dominated the court and ordered the men deported. They were quickly forced onto a steamboat with Charles Perkins’s representatives. One unconfirmed news report claimed they escaped from their captors while the ship was docked in Panama, but their fate is unknown.

California Book of Statutes, 1852, Chapter 33: Respecting Fugitives from Labor, and Slaves brought to this State prior to her admission into the Union: “When a person held to labor in any State or Territory of the United States under the laws thereof, shall escape into this state, the person to whom such labor or service may be due, his agent or attorney, is hereby empowered to seize or arrest such fugitive from labor, or shall have the right to obtain a warrant of arrest for such fugitive.Read statute

Read full statute Court Ruling: The State of California has certainly not entered into any contract with free negroes, fugitives, or slaves, by providing in the constitution that neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall exist in this State, which would prevent her, upon proper occasion, from removing all or any one of these classes from her borders.Read full court ruling

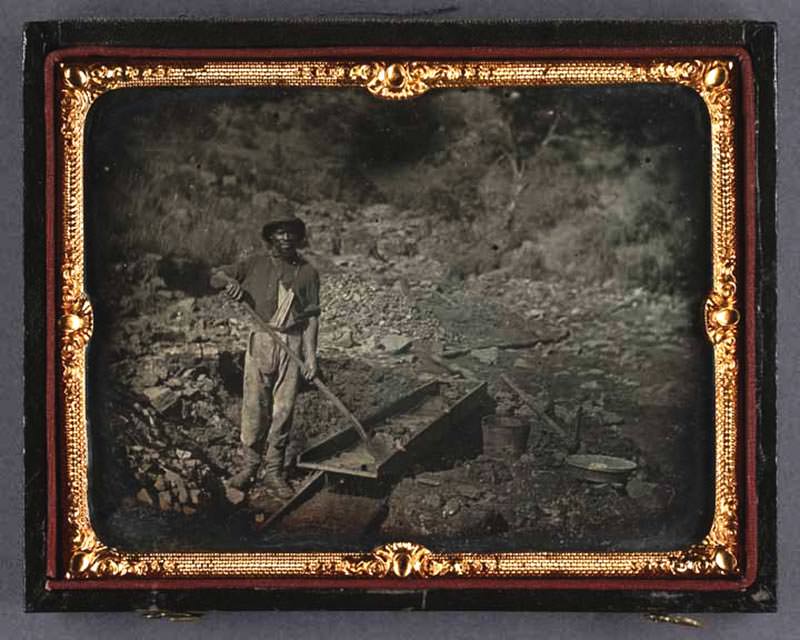

Photo: Black miner during Gold Rush era

Credit: Courtesy of the California History Room,

California State Library, Sacramento, California

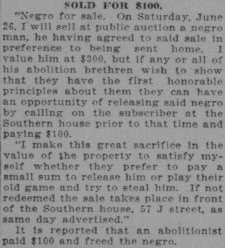

Photo: Advertisement for black slave, originally published in San Francisco Herald / Credit: Sacramento Union, Volume 211, Number 44, 14 December 1919, Courtesy of the California Digital Newspaper Collection, Center for Bibliographic Studies and Research, University of California, Riverside